This is the d'var torah I gave yesterday at Ansche Chesed about the robes of the High Priest.

Shabbat Shalom!

Shabbat Shalom!

When Jeremy asked me to give today’s d’var torah, it seemed like a perfect fit. This parasha describes the clothing worn by the Cohen Gadol, and as some of you know, I make Jewish ritual objects in fabric, including garments like tallitot and kittles.

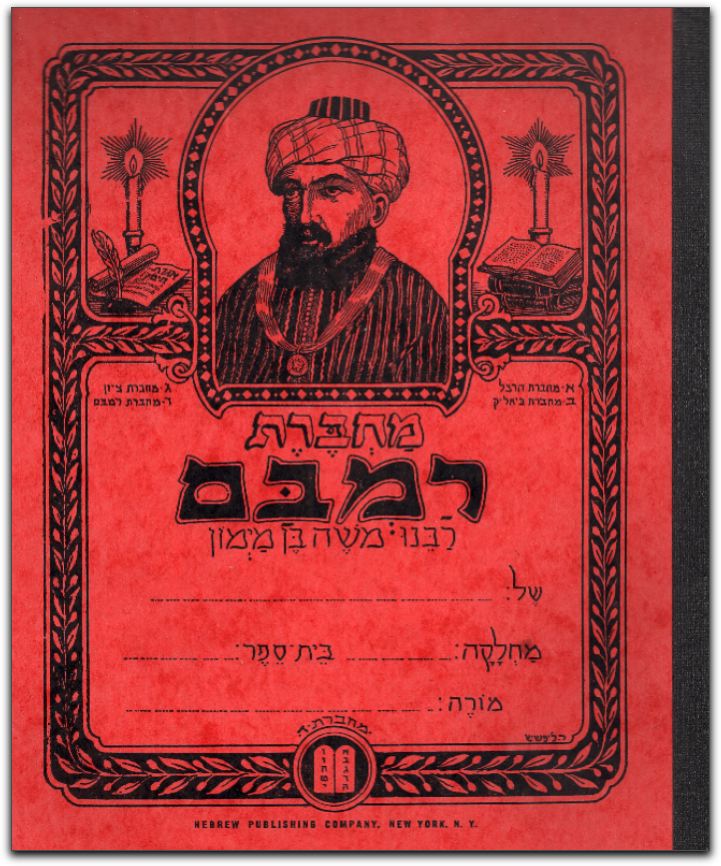

So when I started to think about this dvar torah, the first question I asked myself was the most basic – what did the Cohen Gadol’s garments actually look like? We all have some idea in our head about what the Cohen Gadol wears, ideas generally influenced by pictures we have seen in our Hebrew School textbooks and haggadot. We know there is some kind of a hat, either like a pope’s pointy hat or like the turban worn by the machberet RAMBAM, as well as a breast plate, various layers of robes, and his hem is decorated with pomegranates and bells.

Okay. So, to get a better idea, I went to Google Images and searched for “high priest robes.” I found all sorts of different images, including costumes for kids, available both with and without a beard. There were also costumes for adults, mostly from Messianic Christian sites. It seems that the Cohen Gadol is an important figure for them, although I couldn’t tell you exactly how or why.

But I soon realized that if I really wanted to understand what the Cohen Gadol looked like, Google Images wasn’t the place to go. Rather, the best place to start was to look at the text itself. I began to read.

The description of the garments of the Cohen Gadol begins in Shmot, Chapter 28, verse 4. It says,

And these are the garments which they shall make: a choshen, a breastplate; and an ephod, an ephod; and a m’il, a robe or coat; and a ktonet tashbetz, a tunic of chequer work; a mitznefet, a mitre; and an avnet, a girdle. These are the holy garments for Aaron, and his sons, so they may minister to God in the priest's office.

But what really are all those things? As it turns out, there are some questions about what they are. So, I did what anyone who went to yeshiva would do, I looked at Rashi.

First, Rashi answers the question we might have about the Choshen. He explains that it is a piece of jewelry worn against the heart.

But in his next bit of commentary, we find that even Rashi is rather stumped about the meaning of the word “ephod.” He says,

ואפוד.

לֹא שָׁמַעְתִּי וְלֹא מָצָאתִי בַּבָּרַיְתָא פֵּרוּשׁ תַּבְנִיתוֹ, וְלִבִּי אוֹמֵר לִי שֶׁהוּא חֲגוֹרָה לוֹ מֵאֲחוֹרָיו,

I didn’t hear or find in a braitha an explanation of its structure;

But my heart tells me that it is something that is wrapped around from behind.

What??? Rashi doesn’t know what this word means …so he makes a guess???

Rashi then goes on to describe what he supposes an ephod might be. He describes it as being similar to the aprons women wear when riding horses. Yes, this did send me down a rabbit hole of research. I learned that women in France in the 11th century rode horses astride and not sidesaddle and so they wore voluminous aprons to protect their modesty. Who knew???

So Rashi envisions something that he is familiar with. But that doesn’t say what it actually was.

But then the situation gets even a little more confusing.

Ever since I began to read, I have been reading books on how to make things. I have a collection of old sewing books at home with no photos, and no illustrations, just descriptions of how to put things together, so, I am pretty good and figuring out how to make things just from written directions.

But if you go back and read the text for yourself, you find that it’s really impossible to understand how all this stuff fits together. First, you get a description that gets part way through different elements of the Cohen’s garments as an ensemble. But that is followed by another description, that starts over from the beginning, but whose details are just a little bit different. And just as you think you can figure out where all of the rings and straps and stones fit in relation to one another, there is another list of rings and straps and stones that is, again, just slightly different.

It feels like you are putting together an IKEA dresser but instead of having the directions from one dresser to work from, you have been given the directions to assemble three completely different dressers, and those direction sheets for assembling the three dressers have been randomly ripped apart and stapled together. The task of figuring out how to put together that IKEA dresser, or the garments of the Cohen Gadol, is kind of impossible.

So how are we to understand these competing descriptions? Back to Rashi. Amazingly, he says in his commentary, “Ignore the text and I will tell you how it works” and then he comes up with a coherent idea of what the Cohen Gadol’s uniform looked like.

So, in fact, Rashi realizes that the text is too inconsistent for the reader to make sense of it! And of course, he is very invested in assuring us that the text is perfect, so it all fits together perfectly.

But there is another way to understand what is really going on here. I remember sitting in my father’s synagogue when I was maybe ten or so. My father, a JTS graduate, LOVED modern biblical criticism. He talked about how whatever text we were reading that Shabbat was J or E or P or D, the various redactors of the Torah as envisioned by modern scholars. I remember thinking, “Boy that is so interesting!” But I also remembered that my teachers had taught me that if you don’t believe that the Torah was given all of a piece at Mount Sinai, you lost your Chelek, your place in Olam Ha-ba. As interesting as J and P and E were, I really didn’t want to lose my chelek so I decided not to believe that it was possible that there was more than one author of the Torah and that it was a compiled manuscript.

But when I look at texts like this one today, it’s hard not to see that this is a collection of texts cut and pasted together, and rather roughly stapled together at that.

And, as Biblical scholars tell us, many of the P, or priestly, texts were written at a much later date.

This made me think of another book I read. About twenty years ago, a collection of recipes was published, called In Memory’s Kitchen. The recipes were written by women prisoners in the Terezin concentration camp. They were starving. They had little to no food to eat, but they said that they ate in their minds. These recipes were written down by them in Terezin in the hope that someday they would return to their old lives cooking plentiful foods for the people they loved. Similarly, these priestly texts were written down years later, probably in exile, and possibly from memory, in the hopes of our once again having a beit ha mikdash that would need to be fully accessorized. Like our text here, many of the recipes in that collection are missing essential ingredients, essential steps to allow them to be actually made.

And so, although we don’t know exactly what the garments looked like, in the text itself we learn something very interesting. We read that the materials used to make the garments are in fact the same materials that are used to build the mishkan. The techelet,the blue, the argaman,the purple the tolaat ha shani, the crimson and the gold in the garments are all used in the mishkan. The Cohen Gadol is in fact dressed like the mishkan. It would be as if we had Jeremy wear a suit made out of the sanctuary cushions with a hat made out of one of the stained-glass windows. The Cohen is the embodiment of the mishkan – he is the mishkan in human form for b’nai yisrael.

As Jews, we no longer dress our clergy in fancy robes. Here at Ansche Chesed, Jeremy is not fabulously robed, he wears a really nice tallit.

But in Christianity, and especially in the Catholic church, the image of the priest in his grand robes is still very important. The Church loves the pageantry and splendor that encompassed the Cohen Gadol.

Everyone who visits Italy has their own must-see list. Some have the Colosseum, some have the Sistine Chapel. My list included the stores just outside the walls of the Vatican, where the pope, as well as the cardinals, bishops and other priests, buy their clothes. Visiting those stores was truly one of the highlights of my trip.

These stores offer an amazing array of vestments. They have robes in brilliant purples and crimson and bright greens, as well as creamy whites and shiny gold. Most of these garments are made out of marvelous, richly embellished textiles. Some are elaborately patterned, some have exquisite hand embroidery. Each season requires a different color, and so there are different liturgical robes for this, too. Some of the styles are abstract and starkly modern; others looked like they could have been made during the Renaissance. But in sum, the church likes their officiants to be blinged out like the Cohen Gadol. Seeing and touching so much exquisite thoughtful needlework was just a blast.

These stores offer an amazing array of vestments. They have robes in brilliant purples and crimson and bright greens, as well as creamy whites and shiny gold. Most of these garments are made out of marvelous, richly embellished textiles. Some are elaborately patterned, some have exquisite hand embroidery. Each season requires a different color, and so there are different liturgical robes for this, too. Some of the styles are abstract and starkly modern; others looked like they could have been made during the Renaissance. But in sum, the church likes their officiants to be blinged out like the Cohen Gadol. Seeing and touching so much exquisite thoughtful needlework was just a blast.

As I said, as Jews we shy away from that. And yet, we still have ways in which we evoke the wonderful clothing of the Cohen Gadol. The first of these is right here in this room, in how we dress our sifrei Torah. Our Torah scrolls wear crowns and breastplates, and are garbed in velvets and often embellished in gold. Bells and fringe are also usually part of how we dress our sifrei torah.

And then, there is another time that we recall the garments of the Cohen Gadol. There is a time when we all are dressed like Kohanim, and that is in our graves. Although our tachrichim, our shrouds, are the exact opposite of rich fabrics –, they are plain white and as simple and flimsy and poorly sewn as can be – all the names for the individual garments of the tachrichim, are the same as those of the Cohen Gadol. When we die, we are lovingly dressed like a Cohen in michnisayim, breeches; in a k’tonet, a tunic; in a m’il, a coat; in a hat called a mitznefet, and with a belt, called an avnet.

Shabbat Shalom.

This is so fascinating! Thank you for putting it here for others to think about.

ReplyDeleteGlad you liked it. It was a fun talk to give.

ReplyDeleteTraditionally you read the text with Rashi as your commentator of first choice at your side. he lived from 1040- 1105 in Troyes, France where he earned his living as a wine merchant...on the side(!) he wrote a commentary on the entire bible and Talmud. It would have been a monumental task even if it were a terrible commentary but he collects and transmits earlier traditional commentaries all in the briefest of prose.